- AdQuick Newsletter

- Posts

- Building a Real-World Recommendation Engine for OOH

Building a Real-World Recommendation Engine for OOH

Deeper insight into how AdQuick works

Recommendation systems are usually discussed in the context of content feeds, e-commerce, or ads served in milliseconds. Far less attention is given to recommendation problems where decisions are discrete, expensive, spatially constrained, and operationally irreversible.

Out-of-Home (OOH) advertising is one of those domains.

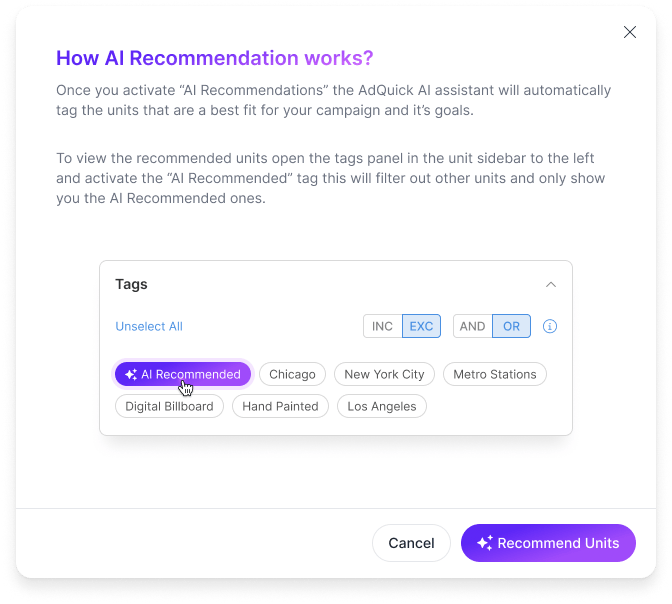

This post walks through how we at AdQuick designed a production-grade recommendation engine for OOH media planning—one that operates under real-world constraints, integrates probabilistic modeling, and bridges optimization with measurement. While the domain is physical media, the architectural lessons generalize to many applied ML problems.

The Problem: Planning Under Physical Constraints

OOH planning is not a ranking problem. You’re not choosing the best item—you’re constructing a portfolio of physical units (billboards, screens, placements) subject to constraints that look more like operations research than recommender systems:

Fixed inventory with heterogeneous attributes

Hard budget caps and pricing granularity

Geographic coverage requirements across multiple markets

Media-type and format allocation bounds

Diminishing returns from spatial and audience overlap

Uncertain outcomes that must later be measured and defended

Traditional approaches rely on heuristics:

Pick “high impressions” units

Spread them out “enough”

Apply manual rules of thumb

The result is fragile plans that are difficult to justify, optimize, or scale.

Reframing the System: Recommendation as Constrained Optimization

We reframed the problem as constrained recommendation rather than prediction.

The engine’s goal is not to predict a single KPI, but to select a set of units that maximizes expected value while satisfying constraints. That required four foundational layers:

A normalized unit representation

A probabilistic reach and overlap model

A scoring function for tie-breaking

A constraint-aware selection algorithm

Each layer is independently testable and evolvable.

Layer 1: Unit Normalization and Feature Control

The system starts with a curated, strongly-typed unit feature space. This is intentionally conservative.

Only features that are:

stable over time

auditable

explainable to non-ML stakeholders

are allowed into the model. Examples include physical dimensions, orientation, illumination, geography, impressions, and supplier metadata.

This decision trades raw model expressiveness for operational trust—a recurring theme in applied ML.

Layer 2: Probabilistic Reach Instead of Deterministic Impressions

OOH impressions are not additive. Two nearby billboards with overlapping traffic do not double reach.

To handle this, the engine models reach probabilistically:

Each unit contributes incremental reach

Incremental value decays with spatial proximity and audience overlap

Overlap is estimated using distance-based decay functions and geo-resolution buckets

Rather than estimating exact people reached, the model estimates expected incremental contribution. This keeps the system fast, monotonic, and directionally correct—crucial for planning.

The key insight:

You don’t need perfect reach to make better decisions—you need consistent marginal comparisons.

Layer 3: Predicted Engagement as a Tie-Breaker, Not a Target

Many recommender systems collapse under the weight of trying to predict a single “true” outcome.

We explicitly avoided that.

Instead, we introduced a Predicted Engagement Score (PES) used only when two candidate units are otherwise equivalent on constraints and reach contribution. PES never overrides hard constraints or reach logic—it resolves ambiguity.

This design keeps the system robust even when the engagement model is imperfect, which it always is.

Layer 4: Constraint-Aware Selection

The selection algorithm is iterative and greedy—but not naive.

At each step, the engine evaluates:

Remaining budget

Media-type allocation bounds

Market coverage requirements

Marginal reach contribution after overlap

Optional soft preferences

Candidates that violate hard constraints are excluded outright. Among the rest, the engine selects the unit with the highest incremental value per dollar.

This approach scales linearly, remains interpretable, and avoids the brittleness of global solvers that struggle with noisy inputs.

Measurement as a First-Class Citizen

A critical design choice: the planner and the measurement system share definitions.

Units selected by the engine are later evaluated using the same geographic primitives, cohort definitions, and exposure logic. That alignment eliminates a common failure mode where optimization and measurement disagree by construction.

The result is a closed loop:

Plan → Measure → Learn → Update heuristics and weights

Notably, this loop improves system behavior even without retraining complex models.

Why This Matters Beyond OOH

This project reinforces several broader lessons for ML practitioners:

Optimization problems benefit from humilityDirectionally correct models with clear constraints often outperform brittle “perfect” predictors.

Explainability is a feature, not a concessionSystems that stakeholders trust get used—and improved.

Measurement alignment beats model complexityShared definitions across planning and evaluation compound over time.

Most recommendation problems are actually portfolio problemsTreating them as such unlocks better architectures.

Closing Thought

The most interesting ML systems live at the boundary between theory and reality—where constraints are messy, data is imperfect, and decisions have consequences.

Recommendation engines don’t need to be magical. They need to be honest, measurable, and designed for the world they operate in.

That’s the standard we held ourselves to—and the one worth aiming for in any applied ML system.

Learn more about AdQuick on our website